Preventing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Across the Lifespan

Preventing Domestic Violence and Intimate Partner Violence is a Priority. IPV is a serious preventable public health problem that affects millions of Americans and occurs across the lifespan.2-4 It can start as soon as people start dating or having intimate relationships, often in adolescence. IPV happens when individuals first begin dating, usually in their teen years, is often referred to as TDV. To arm yourself with the professional tools needed to support victims, enroll in the “Spousal/Partner Abuse Detection and Intervention” course with Aspira Continuing Education.

From here forward in this technical package, we will use the term IPV broadly to refer to this type of violence as it occurs across the lifespan. However, when outcomes are specific to TDV, we will note that. IPV (also commonly referred to as domestic violence) includes “physical violence, sexual violence, stalking, and psychological aggression (including coercive tactics) by a current or former intimate partner (i.e., spouse, boyfriend/ girlfriend, dating partner, or ongoing sexual partner).”5 Some forms of IPV (e.g., aspects of sexual violence, psychological aggression, including coercive tactics, and stalking) can be perpetrated electronically through mobile devices and social media sites, as well as, in person. IPV happens in all types of intimate relationships, including heterosexual relationships and relationships among sexual minority populations.

Family violence is another common term we use in prevention efforts. While the term domestic violence encompasses the same behaviors and dynamics as IPV, the term family violence is broader and refers to a range of violence that can occur in families, including IPV, child abuse, and elder abuse by caregivers and others. This package is focused on IPV across the lifespan, including partner violence among older adult populations. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has developed a separate technical package for the prevention of child abuse and neglect.6 IPV is highly prevalent. IPV affects millions of people in the United States each year.

Data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey

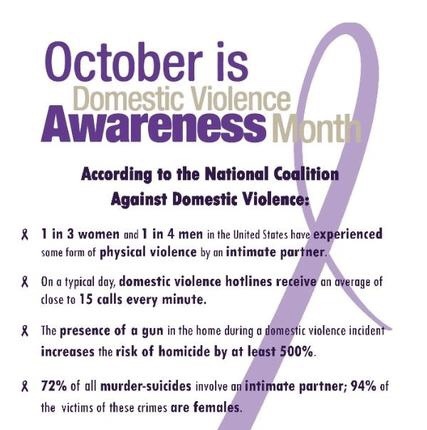

Data from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS) indicate that nearly 1 in 4 adult women (23%) and approximately 1 in 7 men (14%) in the U.S. report having experienced severe physical violence (e.g., being kicked, beaten, choked, or burned on purpose, having a weapon used against them, etc.) from an intimate partner in their lifetime. Additionally, 16% of women and 7% of men have experienced contact sexual violence (this includes rape, being made to penetrate someone else, sexual coercion, and/or unwanted sexual contact) from an intimate partner.

Ten percent of women and 2% of men in the U.S. report having been stalked by an intimate partner, and nearly half of all women (47%) and men (47%) have experienced psychological aggression, such as humiliating or controlling behaviors.3 The burden of IPV is not shared equally across all groups; many racial/ethnic and sexual minority groups are disproportionately affected by IPV. Data from NISVS indicate that the lifetime prevalence of experiencing contact sexual violence, physical violence, or stalking by an intimate partner is 57% among multi-racial women, 48% among American Indian/Alaska Native women, 45% among non-Hispanic Black women, 37% among non-Hispanic White women, 34% among Hispanic women, and 18% among Asian-Pacific Islander women.

The lifetime prevalence is 42% among multi-racial men, 41% among American Indian/Alaska Native men, 40% among non-Hispanic Black men, 30% among non-Hispanic White men, 30% among Hispanic men, and 14% among Asian-Pacific Islander men.3 Additionally, the NISVS special report on victimization by sexual orientation demonstrates that some sexual minorities are also disproportionately affected by IPV victimization; 61% of bisexual women, 37% of bisexual men, 44% of lesbian women, 26% of gay men, 35% of heterosexual women, and 29% of heterosexual men experienced rape, physical violence, and/or stalking from an intimate partner in their lifetimes.7

People living with disabilities

In regards to people living with disabilities, one study using a nationally representative sample found that 4.3% of people with physical health impairments and 6.5% of people with mental health impairments reported IPV victimization in the past year.8 Studies also show that people with a disability have nearly double the lifetime risk of IPV victimization.9 IPV starts early in the lifespan. Data from NISVS demonstrate that IPV often begins in adolescence. An estimated 8.5 million women in the U.S. (7%) and over 4 million men (4%) reported experiencing physical violence, rape (or being made to penetrate someone else), or stalking from an intimate partner in their lifetime and indicated that they first experienced these or other forms of violence by that partner before the age of 18.3 A nationally representative survey of U.S. high school students also indicates high levels of TDV.

Youth Risk Behavior Survey

Findings from the 2015 Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that among students who reported dating, 10% had experienced physical dating violence and a similar percentage (11%) had experienced sexual dating violence in the past 12 months.10 In an analysis of the 2013 survey where the authors examined students reporting physical and/or sexual dating violence, the findings indicate that among students who had dated in the past year, 21% of girls and 10% of boys reported either physical violence, sexual violence, or both forms of violence from a dating partner.11 While the YRBS does not provide national data on the prevalence of stalking victimization among high school students, we know from NISVS that nearly 3.5 million women (3%) and 900,000 men (1%) in the U.S. report that they first experienced stalking victimization before age 18.3

A study conducted in Kentucky suggests that nearly 17% of high school students in that state report stalking victimization, with most students indicating that they were most afraid of a former boyfriend or girlfriend as the stalker.12 Research also indicates that IPV is most prevalent in adolescence and young adulthood and then begins to decline with age,2 demonstrating the critical importance of early prevention efforts.

Preventing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Across the Lifespan

The current evidence suggests the following approaches to prevent future experiences of IPV and lessen or reduce the negative consequences experienced by IPV survivors: Victim-centered services include shelter, hotlines, crisis intervention and counseling, medical and legal advocacy, and access to community resources to help improve outcomes for survivors and mitigate long-term negative health consequences of IPV.

Services are based on the unique needs and circumstances of victims and survivors and coordinated among community agencies and victim advocates. Housing programs that support survivors in obtaining rapid access to stable and affordable housing reduce barriers to seeking safety.22 Once this immediate need is met, the survivor can focus on meeting other needs and the needs of impacted children. These programs can include access to emergency shelter, transitional housing, rapid rehousing into a permanent home, flexible funds to address immediate housing-related needs (e.g., security deposits, rental assistance, transportation), and other related services and supports.

First responder and civil legal protections. These approaches provide increased safety for survivors and their children after violence has occurred. Included here are law enforcement efforts designed to help survivors and decrease their immediate risk for future violence, orders of protection, and supports for children. These protections address survivors’ immediate and long-term needs and safety.Patient-centered approaches recognize the importance of universal prevention education, screening, and intervention for IPV, reproductive coercion, and other behavioral risks.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening women of childbearing age for IPV and referring women who screen positive to intervention services. 146 Women may be screened for IPV and other behavioral risk factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol, depression) and may also be screened for reproductive coercion and educated about how IPV can impact health and reproductive choices (contraceptive use, pregnancy, and timing of pregnancy). However, not all survivors disclose experiences with violence and there are also opportunities within health care settings to offer universal education on healthy relationships, potential signs of abuse, and available resources and support.

Universal prevention education, screening, and intervention may occur in health care settings but may also be considered in the context of other intervention or program models. Intervention services may include counseling, health promotion, patient education resources, referrals to community services and other supports tailored to a patient’s specific risks. Treatment and support for survivors of IPV, including TDV. These approaches include a range of evidence-based therapeutic interventions conducted by licensed mental health providers to mitigate the negative impacts of IPV on survivors and their children.

These interventions are designed to be trauma-informed, meaning that they are delivered in a way that is influenced by knowledge and understanding of how trauma impacts a survivor’s life and experiences long-term.147 Treatments are intended to address depression, traumatic stress, fear and anxiety, problems adjusting to school, work or daily life, and other symptoms of distress associated with experiencing IPV.

Get Certified and Help Prevent Intimate Partner Violence

Aspira Continuing Education’s certified IPAEP offers profound insights into the root causes of IPV and equips professionals with the tools to support victims. To gain a deeper understanding of IPV and how to contribute to its eradication, visit Aspira Continuing Education and enroll in the “Spousal/Partner Abuse Detection and Intervention” course. We encourage professionals and the public to engage with this material and contribute to the efforts to end domestic violence.

For more information or a free social work continuing education course on Spousal Partner Abuse Detection and Intervention CE Course

please visit our course listing page at Online counselor continuing education courses

For more information on Preventing Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) Across the Lifespan, click here.