They “talk” with anonymous strangers in chat rooms and news groups; “visit” museums and African plains; “kiss,” “hug” and “have sex” by typing into a computer; “swim underwater” in simulated oceans.

It’s a new world, all right—one in which we are confronted daily with new emotional issues, or new twists on age-old issues. These three brief vignettes illustrate some of the uncharted waters we are wading in today.

Real Life vs. Net Life

George spends five to eight hours a day on the Internet talking with a vast assortment of friends in various chat communities. He presents himself alternately as an assertive and confident Casanova, an opinionated scholar or a focused, take-charge businessman.

In “real life,” George is none of these. Painfully shy and extremely self-critical, George keeps to himself.

“I feel more like myself when I’m online,” he says. But what he really means is, “I feel more like who I wish I was.”

In online culture, people often use the anonymity to put forth an alternate “self.” Internet interactions don’t carry the same risks as face-to-face conversations. And that can free people to explore previously underdeveloped parts of themselves.

But without integrating those new parts into real life, identities remain dependent on a machine. The computer becomes simply a safe haven in which to hide. And boundaries between the imagined world and real world become further blurred.

Virtual Infidelity (Internet Addiction)

Every time Cynthia’s husband heads upstairs to the office, her stomach tightens and her jaw clenches.

“I feel paranoid whenever he is on the computer,” she says. “I can’t get it off my mind that he is cheating.”

Cynthia confronted Victor after reading an email from a woman she had never heard of, who apparently lived in another country. Victor denied having an affair. After all, he had never actually seen the other woman, much less touched her, and he had no plans to do so. “A bunch of typed words don’t amount to an affair,” he maintained. It was just talking and exploring fantasies.

But to Cynthia, the intimacy expressed in the email is more threatening than a purely sexual relationship. She wondered why her partner couldn’t be that intimate with her.

Intimacy issues are often at the heart of Internet affairs. Too often, however, online time serves only to distract from the marital problems at hand. And online relationships are generally easier because of the illusion of perfection. Lack of information about the real person to whom one is talking, the silence into which one types, the absence of visual cues—all these can make the person on the other end of the keyboard seem infinitely more wonderful than the imperfect person who shares your bed.

Simulated Experience

Four-year-old Eddie spends hours behind a computer screen studying whales and porpoises; he can identify almost anything that swims. But Eddie has never seen real fish, though he lives near the ocean and a world-class aquarium.

Like a pint-sized hermit peering out of his window, Eddie, like huge numbers of children today, is learning about nature on a computer screen, not from direct contact with the natural world. His experience is only a simulated experience, which increasing numbers of people are willing to accept as sufficient.

And yet, watching elms shimmer in the bright fall sunshine on a flashy website is not the same as actually strolling through a wood of shimmering elms.

Simulation is seductive; it avoids imperfections, cracks, rough edges. Fake things can seem more compelling than the real.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of balance and awareness. There is no question that computers and the Internet are here to stay. The most important question is: How can we get the best of both?

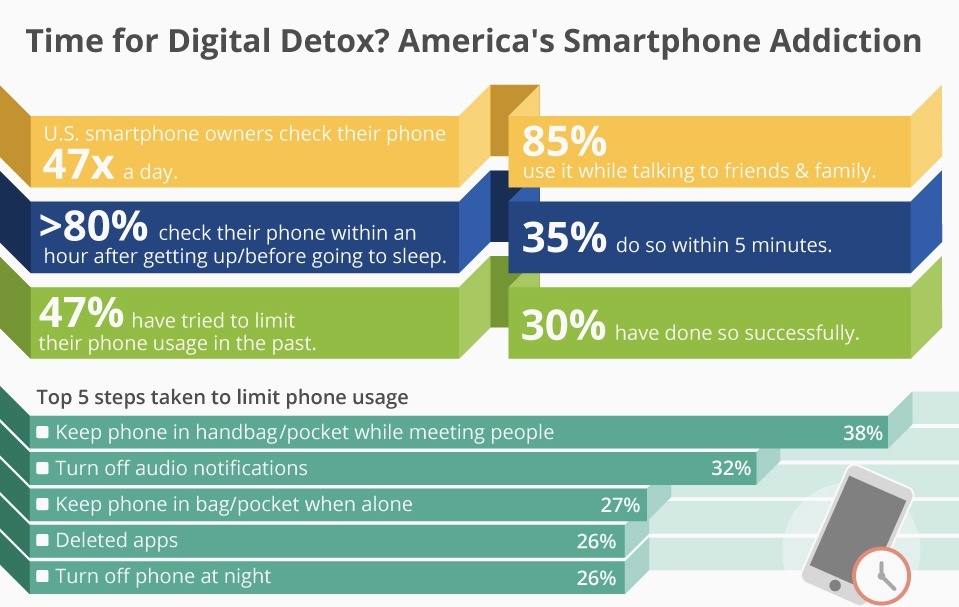

Time Leakage

Handling email and “surfing the Web” can eat hours from each day. Bit by bit, our days dribble away, trickling out our modems. Every hour behind the keyboard is 60 minutes not spent doing something else. During the hours you spend online, you could instead plant a garden, volunteer at a senior citizen’s home, teach your child (or a neighborhood kid) to catch a pop fly, throw a vase on a potter’s wheel. It’s all about balance. Is there something you’d feel better about doing?

When the Internet Becomes a Problem (Internet Addiction)

People get addicted to all sorts of things: drugs, eating, gambling, exercising, spending, sex, etc. Problematic addiction can be defined as anything that never really satisfies needs, that ultimately causes unhappiness and disrupts lives. Here are some questions that psychologists offer to people who are trying to determine if they are indeed addicted (including internet addiction):

• Are you neglecting important things in your life because of this behavior?

• Is this behavior disrupting your relationships with important people in your life?

• Do important people in your life get annoyed or disappointed with you about this behavior?

• Do you get defensive or irritable when people criticize this behavior?

• Do you ever feel guilty or anxious about what you are doing?

• Have you ever found yourself being secretive about or trying to “cover up” this behavior?

• Have you ever tried to cut down, but were unable to?

• If you were honest with yourself, would you feel there is another hidden need that drives this behavior?

An affirmative reply to one or two of these responses may not mean anything. An affirmative reply to three or more of them could mean trouble.

Author’s content used under license, © 2008 Claire Communications

For information on our electronic therapy course, please visit ASPIRA CONTINUING EDUCATION ONLINE COURSES or Using Technology-Based Therapeutic Tools in Behavioral Health Services CEU COURSE